Protecting Your Home: A Practical Guide to Household Pests in Australia

Australia’s diverse climates – from the tropical north and humid east to the arid centre and temperate south – support an equally diverse range of household pests. Rainforest areas harbour mosquitoes, ticks and midges; termite mounds pepper the tropics; coastal cities host feral pigeons and Indian myna birds; and cooler southern states contend with ants, rodents, cockroaches and silverfish. These organisms have evolved to exploit human environments and can become serious nuisances, cause structural damage or threaten health. Understanding their biology and behaviour is the first step to controlling them.

Household pests are not random invaders. They thrive where they find shelter, moisture and food. Ants forage for sugary spills, cockroaches feed on crumbs and grease, mice nest in cluttered storage and termites silently consume wooden frames. Flies breed in refuse, while mosquitoes lay eggs in stagnant water. Some species – such as European wasps and redback spiders – possess stings or bites that can harm people, and others transmit disease. Control efforts must therefore balance safety, cost and environmental impact.

This article aims to be a comprehensive reference on household pests in Australia. It explains how common species live, the health risks they pose and evidence‑based strategies for prevention and control. Wherever possible statistics are used to illustrate the scale of problems – for instance, termites are estimated to attack 130 000–180 000 homes each year, and bed bug reports surged by 4 500 % across Australia between 1999 and 2006. The guide also explores emerging challenges such as Ross River virus outbreaks, climate change and increasing urbanisation. Whether you are a home‑owner, tenant or property manager, you will find practical advice on protecting buildings and health while minimizing harm to the environment.

Finally, the book concludes with a profile of Pestrol Australia. Founded over two decades ago, Pestrol markets safe, do‑it‑yourself pest control products and has become one of the largest providers of alternative pest control solutions in the country. Understanding the range of products and services available helps consumers make informed decisions about pest management.

Understanding Termites

Biology and Species Diversity

Termites are social insects belonging to the order Isoptera. Over 350 species occur in Australia, although only about forty cause significant damage to timber structures. Termites live in colonies comprising reproductive kings and queens, soldiers and workers. The queen may live for 15–50 years and produces thousands of eggs. Workers carry out foraging and construction and are responsible for digesting cellulose. Soldiers defend the colony using enlarged heads and mandibles or chemical secretions.

Termites are often confused with ants because both are social and wingless at most life stages. They differ in anatomy and diet: termites have straight antennae and broad waists, whereas ants have elbowed antennae and narrow waists. Termites feed exclusively on cellulose, digesting wood, paper, cardboard and leaf litter, while most ants are omnivorous.

Major Destructive Groups

Three main groups of termites cause structural damage in Australian homes:

- Subterranean termites form large colonies underground and build mud tubes to travel unseen between soil and wood. Species such as Coptotermes acinaciformis are among the most destructive, attacking framing, flooring and furniture. They maintain contact with moisture and can travel long distances underground.

- Drywood termites live entirely within timber and do not require soil contact. They infest furniture and roof timbers, producing dry pellet‑like droppings. Because colonies are smaller, damage often goes unnoticed until advanced.

- Dampwood termites prefer decaying or damp timber and are less common in buildings. Nonetheless, poorly ventilated crawl spaces and damp retaining walls can attract them.

Scale of the Termite Problem In Australia

Termites are estimated to infest around one in five Australian homes, causing structural or cosmetic damage to 130 000–180 000 houses each year. They can compromise structural integrity within 12 months, and because damage develops internally it often remains hidden until significant. Unlike storms, floods or fires, termite damage is not covered by most building insurance policies. Cost estimates vary, but nationwide repair bills run into hundreds of millions of dollars annually.

Detecting and Preventing Termite Infestations

Early detection is essential. Signs include:

- Mud tubes running over foundations or internal walls.

- Hollow‑sounding timber when tapped.

- Papery or blistered paint surfaces.

- Accumulations of termite droppings (frass) under wood.

Preventive measures involve reducing wood‑to‑soil contact, improving drainage and ventilation, removing wood debris and conducting regular professional inspections. Chemical barriers around foundations and baiting systems can intercept foraging workers. During construction, physical barriers such as stainless‑steel mesh or graded stone layers deter termite entry. The use of treated timber also reduces susceptibility.

Termite Treatment options

Treatment depends on species and extent. Professional pest managers employ insecticidal soil treatments, baiting systems or a combination. Baits contain insect growth regulators that workers carry back to the colony, disrupting development. Physical removal of infested timber and replacement with treated wood may be necessary. Home‑owners should avoid DIY chemical treatments unless they understand the product and follow safety directions.

Ants: Tiny Invaders with Big Impacts

General Ant Biology

More than 4 000 ant species are known in Australia. Ants live in colonies that can range from a few dozen to millions of individuals and consist of castes including queens, workers and, in some species, soldiers. Queens lay eggs; workers forage and care for young; soldiers defend the colony. Ants communicate via pheromones, leaving chemical trails to guide nest mates to food. Their life cycle has four stages: egg, larva, pupa and adult.

Ants are not closely related to termites despite superficial similarities. They do not eat sound timber and seldom cause structural damage. However, some species may nest in wall cavities or decaying wood and can chew electrical wiring or foam insulation. Ants may also protect sap‑feeding insects such as aphids and scale because they harvest honeydew, indirectly damaging plants.

Major Pest Species

While most native ants are beneficial predators, several introduced or nuisance species become pests in homes. Key species include:

- Argentine ant (Linepithema humile) – a slender brown ant 1.5–3 mm long. Colonies contain many queens and can spread across several hectares; nests are interconnected and produce continuous trails of workers. Argentine ants prefer sweet foods but also eat meat and insects and may invade houses during wet weather.

- White‑footed house ant (Technomyrmex albipes) – shiny black 2.8–3.5 mm long with pale feet. They usually nest outdoors under bark or leaf litter but can establish small colonies indoors near food sources. Trails of workers run along walls and pipes. Baiting or residual sprays may be required for control.

- Black house ant (Ochetellus glaber) – intensely black ants 2.5–3 mm long with an iridescent sheen. They produce a distinctive odour when crushed. Nests occur in soil, tree hollows, ceiling voids and wall cavities; they forage widely and will exploit sugary foods and greasy scraps.

- Pharaoh’s ant (Monomorium pharaonis) – light yellow‑brown to dark brown ants 1.5–3 mm long. They nest in warm areas of buildings, such as heating ducts or near hot water pipes, and have multiple queens. Pharaoh’s ants prefer high‑protein foods and will fragment their colony when threatened. Spraying can cause colonies to split, so baiting is recommended.

- Coastal brown ant (Pheidole megacephala) – light to dark brown; workers 1.5–3 mm and larger soldier caste 3.5–4.5 mm. They favour protein‑rich foods and nest in soil, walls or beneath floors. Multiple queens allow rapid colony growth.

- Carpenter ants (Camponotus spp.) – ranging from 2.5–14 mm long. They nest in decaying wood and moist building materials but rarely damage sound timber. Nocturnal and long‑lived, they can travel far for food.

- Singapore ant (Monomorium destructor) – light brown 1.5–3 mm long and known to damage plastics and electrical wiring, occasionally causing fires.

In addition, red imported fire ants (Solenopsis invicta) pose a major biosecurity threat. These generalist predators reduce biodiversity by displacing native ants and prey on invertebrates and ground‑dwelling vertebrates. They also damage plants by consuming seeds and fruit and can inflict painful stings en masse. Detected in Brisbane in 2001, fire ants are subject to intensive eradication programs because they could spread across much of coastal Australia.

Ant Signs and Management

Ant infestations manifest as trails of workers, nests in soil or building cavities and occasional winged reproductive flights. Control begins with identifying the species because treatments vary. Good hygiene, sealing entry points and removing food sources reduce infestations. Baits containing slow‑acting insecticides are effective because they are carried back to the nest and shared. Outdoor nests can be treated with residual sprays or dusts. For Argentine ants or Pharaoh’s ants, professional pest management may be needed due to colony complexity.

Cockroaches: Survival Experts and Health Risks

Cockroaches have existed for over 300 million years and owe their success to adaptability and generalist feeding. Several species have become serious household pests in Australia, including the German cockroach (Blattella germanica), American cockroach (Periplaneta americana) and Oriental cockroach (Blatta orientalis). Adults range from 1.5 cm to over 5 cm long, possess leathery wings (although most domestic species seldom fly) and have long antennae. They are nocturnal and hide in cracks during the day.

Cockroach Life Cycle and Reproduction

Cockroaches undergo incomplete metamorphosis: eggs hatch into nymphs that resemble adults but lack wings. Nymphs moult several times before reaching maturity. A female cockroach produces egg cases (oothecae) containing between 10 and 40 eggs and may lay around 30 cases during her lifetime. Under favourable conditions, German cockroaches can reach adulthood in 6–8 weeks and survive up to 12 months. Their rapid reproduction means small infestations quickly become large.

Cockroach Health risks

Cockroaches are considered vectors of bacteria and viruses. They scavenge in sewers, rubbish and rotting materials, contaminating food preparation surfaces with pathogens such as Salmonella, Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. They may also trigger allergies and asthma due to airborne shed skins and droppings. Cockroach infestations contribute to unpleasant odours and can damage books and fabrics through excrement and secretions.

Cockroach Prevention and Control

Effective management combines hygiene, exclusion and targeted treatments. Tips include:

- Cleanliness: Vacuum crumbs and grease, wash dishes promptly, wipe surfaces and store food in sealed containers. Eliminate clutter where cockroaches hide.

- Moisture control: Fix leaks and dry damp areas. Cockroaches require water and will congregate near sinks, dishwashers and plumbing.

- Exclusion: Seal cracks, gaps around pipes and door thresholds to block entry. Install fine mesh screens on drains and windows.

- Baiting and trapping: Gel baits containing slow‑acting insecticides are highly effective because cockroaches share food. Sticky traps help monitor numbers.

- Insecticidal sprays or dusts: Residual sprays applied to harbourage areas and dusts injected into wall cavities can reduce populations. Always follow label directions and consider professional treatment for severe infestations.

Rodents: Rats and Mice

Rodent Diversity and Biology

Rodents (order Rodentia) are the most successful mammals after humans, with more than 2 200 species worldwide. Australia hosts over 60 native rodent species and three introduced pest species – the Norway rat (Rattus norvegicus), roof rat (Rattus rattus) and house mouse (Mus domesticus). Their success arises from small body size, rapid breeding and omnivorous diets. Rodent incisors grow continuously and require constant gnawing to prevent overgrowth.

Norway Rat (brown/sewer rat)

This larger pest species has brown or grey fur, a blunt nose, small ears and a heavy build. The head and body measure 20–27 cm, with a shorter tail of 16–20 cm; adults weigh 200–500 g. Females produce 5–6 litters per year, each containing 8–10 pups. Norway rats are omnivorous but prefer starch and protein‑rich foods such as cereals, meat and fish. They are excellent swimmers and diggers and typically nest in burrows, sewers or under rubbish.

Roof Rat (black/ship rat)

Smaller and more agile than Norway rats, roof rats have slender builds, pointed noses and long tails exceeding their head‑body length. Adults measure 14–20 cm with a tail about 25 cm long and weigh 200–300 g. Females produce 4–5 litters of 6–8 pups each year. Roof rats are adept climbers, nesting in roof voids, ceilings and trees. They prefer fruits, grains and nuts but will eat almost anything when food is scarce.

House Mouse

Small and curious, the house mouse measures 8–10 cm with an equal‑length tail and weighs only 14–20 g. Females reach sexual maturity at six weeks and can produce 6–10 litters a year. Mice feed on grains, seeds and household scraps and can squeeze through gaps as small as 8 mm. They often live indoors in wall cavities and cupboards.

Rodent Impacts and Health Risks

Rodents consume and destroy more food than they eat by gnawing and contaminating stores with urine and droppings. Their gnawing can damage electrical wiring, insulation and structures, causing fire risks or costly repairs. Rats and mice are vectors of diseases including leptospirosis, salmonellosis, hantavirus and murine typhus. They may carry ectoparasites such as fleas, which transmit tapeworms and bubonic plague. Because rodent populations can explode under favourable conditions, such as during the 2021 mouse plague in eastern Australia, vigilance is essential.

Identification and Signs of Rodent Infestation

Common signs include:

- Droppings: Norway rat droppings are banana‑shaped, while roof rat droppings are spindle‑shaped; mouse droppings resemble small black grains.

- Gnaw marks and holes: Mice gnaw 20 mm holes in walls; rat holes are larger (80 mm).

- Smudges and tracks: Rodent fur leaves greasy marks along runways.

- Nests: Shredded paper, straw or fabrics hidden in warm areas.

- Noises: Scratching in walls, ceilings or under floors, especially at night.

Rodent Control Methods

Integrated rodent management combines sanitation, exclusion, trapping and baiting:

- Sanitation and exclusion: Maintain high hygiene standards, remove clutter and food scraps, fix plumbing leaks and seal holes and gaps. Store food in rodent‑proof containers and keep rubbish sealed.

- Trapping: Snap traps and multiple‑catch devices can eliminate individuals without poison. Traps should be placed along runways and checked daily.

- Rodenticides: Acute poisons (zinc phosphide, norbormide) and chronic anticoagulants kill rodents through bait ingestion. Always follow safety instructions to protect non‑target animals. Note that some baits act slowly to allow multiple rats to feed before dying.

- Professional assistance: Severe infestations or sensitive settings may require licensed pest controllers who can deploy monitoring stations and manage bait rotation.

Mosquitoes and Mosquito‑Borne Diseases

Australia harbours over 300 mosquito species, many of which play vital roles in ecosystems as pollinators or food for fish and birds. However, several species transmit pathogens, making mosquitoes a public health concern. Warm, wet conditions following rainfall and floods produce ideal breeding habitats, and climate variability such as La Niña events can cause population explosions.

Mosquito Life Cycle and Ecology

Mosquitoes undergo complete metamorphosis: eggs hatch into aquatic larvae (wigglers) that progress to pupae before emerging as flying adults. Females require blood meals to develop eggs, while males feed on nectar. Different species prefer different habitats: Aedes mosquitoes breed in artificial containers and floodwaters, Culex species prefer polluted stagnant water, and Anopheles breed in clean freshwater. Adults are most active at dawn and dusk, although some species feed during the day.

Key Mosquito-borne Diseases in Australia

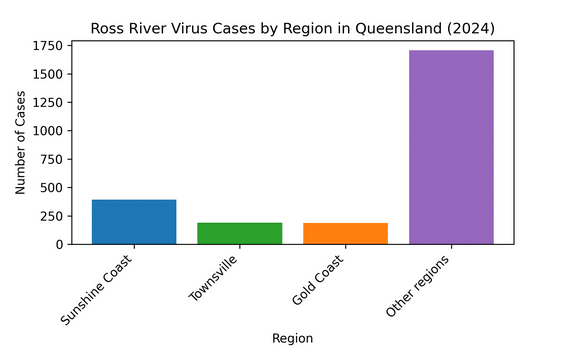

- Ross River virus (RRV): The most common mosquito‑borne disease in Australia, causing fever, rash and debilitating joint pain. Queensland recorded more than 2 000 cases during the 2023–24 season, nearly six times the number in 2023. During the 2024 season the Sunshine Coast alone recorded 392 cases, with Townsville and the Gold Coast registering 190 and 187 cases respectively, while total Queensland notifications reached 2 475 (see chart below). There is no vaccine or specific treatment.

- Barmah Forest virus (BFV): Causes milder symptoms similar to RRV. Cases fluctuate annually and often occur in eastern Australia.

- Dengue fever: Primarily confined to far north Queensland, transmitted by Aedes aegypti. Dengue causes high fever, severe headaches and joint pain. Outbreaks occur when infected travellers introduce the virus and local mosquitoes transmit it. Control relies on eliminating breeding sites.

- Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV): A rare but serious disease causing encephalitis. In 2025 Queensland recorded three human cases of JEV, with two fatalities. The virus was detected in mosquitoes and pigs across the state, including locations where it had not been seen before. JEV is primarily transmitted by Culex mosquitoes, which become infected by biting pigs or water birds. A vaccine is available for at‑risk individuals in affected areas.

- Murray Valley encephalitis (MVE) and Kunjin virus: Sporadic but potentially fatal diseases associated with heavy rainfall and flooding. They occur in northern Australia but can extend south during wet years.

Mosquito Prevention and Control

Mosquito control focuses on reducing breeding sites and preventing bites:

- Eliminate standing water: Tip out or cover containers, unclog gutters and drains, and maintain water tanks and ponds. Larvae need water to develop.

- Personal protection: Wear long sleeves and light‑coloured clothing; apply repellents containing DEET, picaridin or oil of lemon eucalyptus; and use bed nets or screened areas.

- Community measures: Local authorities monitor mosquito populations and test for viruses by trapping adult mosquitoes. In high‑risk areas, larvicides are applied to breeding sites and adult mosquitoes may be targeted with fogging. Education campaigns encourage residents to eliminate breeding habitats.

- Vaccination: At‑risk individuals in areas with JEV can access vaccines provided by public health departments.

Chart: Ross River virus cases in Queensland, 2024

The following bar chart visualises the distribution of Ross River virus cases across Queensland regions in 2024. The majority of cases occurred in regions other than the Sunshine Coast, Townsville and Gold Coast, emphasising that RRV is widespread across the state.

Fleas and Lice

Fleas

Fleas are wingless, blood‑feeding insects 2–8 mm long with laterally flattened bodies and powerful hind legs for jumping. Three species commonly bite humans in Australia: the cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis), dog flea (Ctenocephalides canis) and the human flea (Pulex irritans). Fleas feed on pets and people and can go months without feeding, waiting for vibrations to signal a host. Females lay eggs in the host’s environment; larvae feed on organic debris before pupating. Adult fleas emerge when conditions are favourable and can quickly infest carpets, bedding and furniture.

Flea bites cause intense itching and small red swollen welts that may blister. Scratching can lead to infection. Fleas are vectors of diseases such as murine typhus and can transmit tapeworm larvae to pets. Heavy infestations may cause anaemia in young animals. To manage fleas:

- Treat pets with veterinary‑approved insecticides or growth regulators.

- Wash bedding in hot water and vacuum carpets frequently to remove eggs and larvae.

- Use insecticidal sprays or powders targeting carpets and furnishings.

- Address infestations promptly; otherwise dormant pupae can survive for months.

Lice

Lice are tiny wingless insects that live on hair or feathers. Head lice (Pediculus humanus capitis) are common among schoolchildren and cause itching by feeding on scalp blood. Body lice and pubic lice (crabs) are less common. Lice spread through close contact and sharing of hats or brushes. Treatment involves medicated shampoos containing pyrethrins or insect growth regulators and combing out nits. Washing bedding and clothing in hot water and avoiding head‑to‑head contact reduces transmission.

Ticks and Mites

Paralysis Tick

The Australian paralysis tick (Ixodes holocyclus) is found along the eastern coastline. Females climb vegetation and attach to passing hosts including humans, dogs and wildlife. The bite initially causes itching and a raised lump, but as the tick engorges over several days symptoms can progress to flu‑like illness, unsteady gait, weak limbs and partial facial paralysis. Severe reactions include anaphylactic shock, particularly in individuals with previous tick allergies. Children are more vulnerable because ticks may go unnoticed.

If a tick is found, do not disturb it. Killing the tick on the skin reduces the risk of it injecting more saliva. Adult ticks should be frozen in place with an ether spray until they drop off; larval and nymph stages can be dabbed with permethrin cream. Avoid grasping ticks with fingers or tweezers as this may cause saliva injection. Wear long clothing and apply repellents when in bushy or grassy areas.

Ticks may transmit bacterial diseases such as Queensland tick typhus (Rickettsia australis) and Flinders Island spotted fever. Early symptoms include rash, fever, headache and swollen glands. These illnesses respond to antibiotics, so medical advice is recommended if fever develops following a tick bite.

Mites

Mites are minute arachnids with diverse lifestyles. Dust mites feed on skin flakes and thrive in bedding and carpets; they produce allergens that trigger asthma. Scabies mites (Sarcoptes scabiei) burrow into human skin causing intense itching and rash; they spread through prolonged skin contact. Bird mites occasionally bite humans when nests are abandoned, causing temporary itching. Control involves treating affected humans or pets, washing fabrics in hot water, and sometimes professional fumigation.

Flies and Midges

House flies (Musca domestica) are ubiquitous pests that breed in decaying organic matter. They carry over 100 known pathogens including bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites. Because they feed and breed in faeces, animal manure and refuse, they mechanically transfer pathogens to food and surfaces when they land. Blowflies, flesh flies and fruit flies also create nuisances and may infest wounds or spoil fruit.

Prevention focuses on sanitation: dispose of garbage properly, maintain compost bins, pick up pet droppings and cover food. Screens on windows and doors keep flies out, and electric zappers or UV traps can reduce indoor populations. Insecticidal surface sprays or baited traps offer additional control. To avoid attracting midges, minimise outdoor lights and apply repellents during peak biting times.

Wasps and Bees

European Wasp

The European wasp (Vespula germanica) was introduced to Australia in the 1950s and has become a major pest, particularly in urban areas. Without natural predators, nests can survive through winter and may contain over 100 000 wasps. Workers are about 15 mm long with bright yellow and black markings; queens are larger at around 20 mm. European wasps are aggressive, especially around food, and can sting repeatedly. Stings emit a pheromone that provokes other wasps to attack. Approximately one in ten people stung multiple times will develop an allergy; repeated stings can lead to anaphylaxis.

Native Wasps and Bees

Australia also hosts many native wasps and bees that are important pollinators. Paper wasps build umbrella‑shaped nests under eaves; they can sting but are generally non‑aggressive unless their nest is threatened. Native stingless bees live in tree hollows and rarely cause problems; they are protected in many states.

Control and Safety

For European wasps, nests should be removed by professionals using appropriate protective equipment and insecticidal dusts. Never attempt to burn or flood nests. Avoid leaving food or drinks uncovered outdoors and ensure bins have tight lids. To deter wasps, cover compost heaps and pick up fallen fruit. Bee swarms are best handled by beekeepers, who can relocate colonies safely.

Silverfish and Pantry Pests

Silverfish

Silverfish are primitive, wingless insects measuring 12–19 mm long with tapering bodies and three long tail filaments. Their silvery scales and wiggling movement give them a fish‑like appearance. Silverfish have existed for over 400 million years and can live up to six years. They are nocturnal and thrive in dark, humid environments (above 75 % humidity) at temperatures between 22–30 °C. Their diet includes starch‑rich materials such as paper, glue, wallpaper paste, photographs, book bindings, fabrics and food crumbs, making them destructive to libraries, clothing and stored foods.

Silverfish control begins with reducing humidity through ventilation or dehumidifiers and eliminating food sources by storing books and clothes in sealed containers. Seal cracks in walls or flooring and vacuum regularly. Sticky traps or jar traps baited with bread can capture silverfish. Insecticidal dusts or sprays may be used in severe infestations, but caution is advised around books and fabrics.

Pantry Pests

Pantry pests include flour beetles, weevils, pantry moths and grain borers. They infest stored products such as flour, cereal, nuts and spices. Adults lay eggs directly in food; larvae tunnel through and contaminate products with frass and webbing. Infested items should be discarded; containers cleaned and dried; and new supplies stored in airtight containers. Regularly inspecting pantry stocks helps detect early infestations.

Spiders: Venom, Bites and Benefits

Australia’s reputation for dangerous spiders often overshadows the important role these arachnids play in controlling insect populations. Most of Australia’s 2 000+ spider species are harmless; only a few have venom of medical concern. Interestingly, there have been no confirmed deaths from spider bites in Australia since 1979 thanks to effective antivenoms and public awareness.

Notable Spider Species

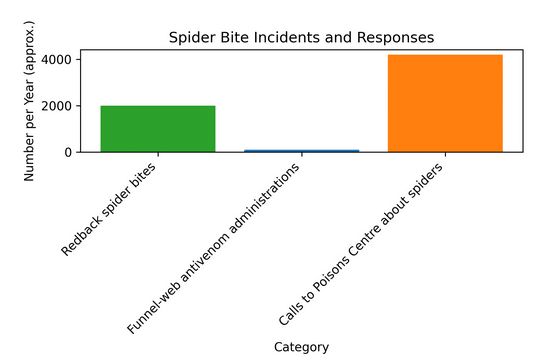

- Redback spider (Latrodectus hasselti): A relative of the American black widow, females have a distinctive red stripe on the abdomen. They inhabit sheds, outdoor toilets and under furniture. Around 2 000 bites are reported annually. Symptoms include pain, sweating, nausea and muscle weakness; antivenom is available.

- Sydney funnel‑web spider (Atrax robustus) and related species: Found in moist forested areas of eastern Australia. Males wander during the warmer months and may enter houses. Their venom can cause severe envenomation; however, antivenom introduced in 1981 has prevented fatalities. At least 100 patients have received funnel‑web antivenom since 1980.

- White‑tailed spiders (Lampona spp.) and wolf spiders: These spiders have been blamed for necrotic bites, although evidence suggests such reactions are rare and secondary infections are more likely.

Bite Management and Prevention

Most spider bites cause localised pain and swelling. Severe reactions are rare but include sweating, nausea or neurological symptoms. First aid involves applying ice packs, elevating the limb and seeking medical attention if symptoms progress. Funnel‑web spider bites require pressure immobilisation and immediate hospitalisation.

Preventive measures include shaking out shoes and clothing, wearing gloves when gardening and sealing gaps under doors. Educating children not to handle spiders reduces risk. Despite fear, spiders provide ecological benefits by preying on cockroaches, flies and mosquitoes; tolerating harmless species can reduce other pests.

Bird Pests: Mynas and Pigeons

Common Myna (Indian Myna)

The common or Indian myna (Acridotheres tristis) is an introduced species that has spread throughout eastern Australia. Community groups and councils have targeted mynas due to concerns that they compete with native birds for food, nesting sites and territory. However, RSPCA Australia notes that research on their impacts remains limited. Some long‑term studies in Canberra suggest mynas negatively affect the abundance of certain native species, but the significance of this impact is debated. Urbanisation appears to favour mynas because they prefer artificial structures over vegetation for nesting.

RSPCA Australia advises that trapping and killing mynas should only occur under government‑supervised programs with humane procedures. Habitat improvement—planting native trees and shrubs—may discourage mynas by providing better resources for native species. Removing food waste and sealing roof cavities also reduces opportunities for nesting. When trapping, ensure humane cages and regular checks to prevent suffering.

Pigeons and Other Birds

Feral pigeons (Columba livia), starlings and sparrows are common urban birds that can foul buildings and balconies with droppings. Accumulated droppings may harbour fungal pathogens such as Cryptococcus and Histoplasma that can cause respiratory illnesses. Birds can also transmit mites and lice. Control options include physical deterrents (spikes, netting, wire), exclusion of nesting sites, removal of food sources and, where necessary, professional trapping. Because many bird species are protected under state wildlife laws, seek advice before implementing control measures.

Possums and Other Urban Wildlife

The common brushtail possum and common ringtail possum are native marsupials that have adapted to urban environments. They nest in roof voids and feed on garden plants. Possums are protected fauna and must not be harmed or relocated without a wildlife permit. While possums are generally not dangerous, their urine and droppings can carry pathogens such as leptospirosis and salmonella. To coexist with possums:

- Seal entry points to roof spaces using wire mesh or timber.

- Trim overhanging branches that provide access to roofs.

- Provide alternative nest boxes in trees to encourage possums to move out of buildings.

- Avoid feeding possums; it is illegal in many states and encourages dependence.

Other urban wildlife, including bats, snakes and lizards, may occasionally enter homes. Bats can transmit lyssaviruses through bites or scratches; professional wildlife carers should handle them. Pythons entering roof spaces can help control rodents but may startle residents. If wildlife becomes a nuisance, contact local fauna rescue organisations for advice rather than attempting to remove animals yourself.

Integrated Pest Management (IPM)

Integrated Pest Management is a holistic approach that combines cultural, physical, biological and chemical methods to suppress pest populations while minimizing risks to human health and the environment. Key principles include:

- Identification and monitoring: Accurately identify pests and understand their life cycles and habits. Monitoring using traps or visual inspection determines population levels and intervention thresholds.

- Prevention: Prevent infestations by improving sanitation, modifying habitats (e.g., reducing moisture or clutter), sealing entry points and choosing pest‑resistant materials. Many pests thrive due to poor hygiene or structural defects.

- Non‑chemical control: Use physical barriers (screens, door seals), traps, heat or cold treatments and biological agents (natural predators or parasites) before resorting to chemicals. For example, nematodes can control soil‑dwelling grubs; diatomaceous earth can desiccate insects.

- Chemical control: When necessary, apply pesticides selectively using baits or spot treatments to target pests. Choose products with minimal non‑target effects and follow label instructions. Rotate active ingredients to prevent resistance.

- Evaluation and education: After treatment, evaluate effectiveness and adjust strategies. Educate occupants about their role in prevention – proper waste management, cleaning and maintenance are crucial to long‑term success.

Employing IPM reduces reliance on broad‑spectrum insecticides, protecting beneficial insects and reducing exposure to toxins. It is also cost‑effective in the long run because prevention and monitoring prevent expensive damage and repeated treatments.

Legal and Environmental Considerations For Pest Management in Australia

Pest control activities in Australia are regulated to ensure public safety and environmental protection. Important considerations include:

- Pesticide use: Only registered pesticides may be sold or used. Users must follow label instructions regarding application rates, personal protective equipment, environmental protection and disposal. Some chemicals are restricted to licensed operators.

- Wildlife protection: Native species, including possums and many birds, are protected. It is illegal to harm or relocate them without authorization. Red imported fire ant eradication is enforced by quarantine zones and movement controls.

- Hazardous devices: Glue traps for rodents are prohibited in some states (e.g., Victoria) because they cause prolonged suffering. Snap traps and live traps must be checked regularly.

- Building codes: New constructions often require termite barriers and appropriate drainage to prevent infestations. Property owners should consult local councils for specific requirements.

- Reporting obligations: Pest managers may need to report certain notifiable pests (e.g., exotic termites or invasive ants) to biosecurity authorities.

Environmental stewardship extends beyond legal compliance. Minimizing pesticide use, protecting pollinators, conserving native predators and adopting sustainable building practices all contribute to healthier ecosystems.

Climate Change and Emerging Pest Threats

Climate change is altering the distribution and behaviour of pests. Warmer temperatures allow mosquitoes and termites to expand southwards and increase the rate at which viruses replicate inside mosquitoes. Extreme rainfall and flooding create breeding sites for mosquitoes, while drought drives rodents and ants indoors in search of water. As winters become milder, more insect pests survive through the season; for example, entire European wasp nests may persist over winter, leading to enormous colonies.

Heat stress and drought also weaken plants, making them more susceptible to sap‑feeding pests. Invasive species may gain a foothold as climate shifts disrupt ecological balances; red imported fire ants and JEV are recent examples. Home‑owners should anticipate changing pest pressures and adapt prevention measures accordingly, such as ensuring rainwater is managed, regularly inspecting for termites and participating in public health monitoring programs.

DIY vs Professional Pest Control

Modern consumers have access to a range of do‑it‑yourself (DIY) pest control products, from bait stations and traps to ultrasonic deterrents and insect growth regulators. DIY approaches can be cost‑effective and convenient for minor infestations, provided users follow instructions carefully. For instance, baiting cockroaches or ants with gel baits can reduce populations significantly. Rodent traps placed correctly can manage occasional mice.

However, professional pest control offers expertise, equipment and access to regulated products. Licensed technicians can identify species accurately, locate hidden nests, select appropriate treatments and ensure safety. They also provide warranties and follow‑up visits. Professional services are advisable when:

- The infestation is extensive or recurring (e.g., termites, Argentine ants or roof rats).

- The pest poses significant health risks (e.g., venomous spiders, wasps, disease‑carrying mosquitoes).

- The structure requires specialized equipment (e.g., fumigation, soil injection).

- Legal obligations require professional treatment (e.g., building inspections for termite protection during property sales).

Ultimately, a combination of DIY prevention and professional intervention yields the best results. Occupants should maintain hygiene, seal entry points and monitor for pests, then consult professionals when necessary.

Pestrol Australia: Your Pest Control Partner

Pestrol Australia is a leading supplier of safe, alternative pest control products. Established more than two decades ago, the company imports and manufactures branded solutions and markets them through radio and television. Pestrol’s philosophy is that homeowners can manage pests effectively with the right products, education and support, reducing reliance on harmful chemicals.

Pestrol offers DIY products across categories:

- Rodent control: Electronic ultrasonic devices, snap traps, bait stations and humane capture cages. A flagship product is the Pestrol Rodent Free MAX, which emits pulses that deter rodents without killing them. Read more: https://www.pestrol.com.au/shop/shop-by-pest/rats-mice/

- Insect control: Mosquito traps using UV light or CO₂ to lure and capture mosquitoes; zappers and repellents; insect growth regulator products for fleas; and bed bug sprays. Their mosquito traps are designed for outdoor use and reduce populations without pesticides. Read more: https://www.pestrol.com.au/shop/shop-by-pest/insect-control/

- Bird and wildlife deterrents: Bird spikes, netting and ultrasonic deterrents that prevent pigeons and mynas from roosting on ledges. Possum deterrents humanely discourage possums from roof spaces. Read more: https://www.pestrol.com.au/shop/shop-by-pest/birds/

- Garden and home products: Natural pest sprays for plants, fertilisers, and cleaning products. Other offerings include portable vacuums, fans and wellness items, reflecting a holistic approach to home care. Read more; https://www.pestrol.com.au/shop/garden/

Pestrol emphasises customer education through online resources, blog articles and technical support. Their website tagline, “DIY Pest Control, Home & Garden Supplies!” underlines the company’s commitment to empowering consumers. Orders over a certain value receive free shipping, and products are backed by warranty. By profiling Pestrol, this guide highlights accessible tools for homeowners seeking safe and effective pest management.

Household pests are a reality of living in Australia’s varied environments. From subterranean termites silently undermining homes to mosquitoes transmitting viruses, each pest presents unique challenges. Understanding their biology, recognising early signs of infestation and implementing integrated prevention strategies form the foundation of successful control. Maintaining cleanliness, managing moisture, sealing structures and improving garden habitats can drastically reduce pest pressure.

Statistics remind us of the magnitude of certain problems: termites affecting up to one in five homes, bed bug infestations increasing 45‑fold between 1999 and 2006, and Ross River virus surging to more than 2 000 cases in a single season. Yet, these numbers also highlight the effectiveness of public health interventions and technological advances—antivenoms have prevented spider‑bite fatalities since 1979, and guidelines for tick removal and mosquito bite prevention reduce disease risk.

No single solution fits all situations. DIY products, such as those offered by Pestrol, provide cost‑effective options for minor infestations. Professional pest controllers bring expertise and access to regulated treatments for complex cases. Working together, homeowners, communities, industry and government can manage pest problems sustainably, protect biodiversity and safeguard human health.

Sources

Images from https://www.pestrol.com.au/

- Compare the Market search data on pest hotspots.

- Newcastle Pest Control statistics on termite damage in Australian homes and details of termite species and categories.

- Australian bed bug resurgence data and bed bug characteristics.

- Pestrol company description, mission and product information, pestrol.com.au.

- Ross River virus detections and mosquito‑borne disease statistics from Queensland Health and additional figures from ABC news.

- Estimated rat populations and rodent health impacts and general rodent biology, reproduction and control methods from Health Victoria.

- Cockroach health risks and life cycles.

- Flea species and bite symptoms.

- Tick bite symptoms and removal guidelines and tick‑borne disease facts.

- House fly disease transmission.

- Silverfish biology and habitat preferences.

- European wasp colony sizes and sting risks.

- Ant biodiversity and general behaviour along with specific species descriptions.

- Red imported fire ant ecological impacts.

- Spider bite statistics and antivenom data.

- RSPCA Australia’s position on myna bird management.

- Mosquito‑borne disease ecology and climate influences.

- Additional citations from accessible government and scientific sources were used throughout to inform context and provide accurate descriptions.